Introduction

This page will go over the relationship between juveniles and the police. We will look at two sides to this relationship. On one hand, the police did outreach trying to dissuade young people from entering lives of crime, and had programs in place to help those who were most vulnerable. On the other hand though, there is a distrust of the police among teenagers which was not helped by a police brutality case against teens in the 80’s. This distrust may have led to some of the lack of reporting we discuss in the Crimes on Teenagers section, and may have led to some police actions not being as successful as they could have been.

Background Info – Canadian Cops and the Youth

Youth crimes have always been something the police in Canada were cognisant of and tried to find ways to stop. The presence of a school liaison officer is not uncommon in our current, post-Columbine shooting world, and existed back in the 1970s and 80s. However, this police presence brings a new problem, the criminalization of offences that without the officer near would be handled purely by school administration and parents.1 Likewise, we see programs like DARE (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) to quell drug use among young adults, and “Scared Straight” projects in America which attempt to scare young offenders with examples of what adult prisons are like.2 Sociologist Julian Tanner notes that “no Canadian government has seriously embraced the sort of deterrence-based programming for young offenders favoured by American politicians.”3 The question then becomes that if Canada did not seriously consider programs like America’s, what do we see from our local police forces in the Fraser Valley?

Outreach in Matsqui

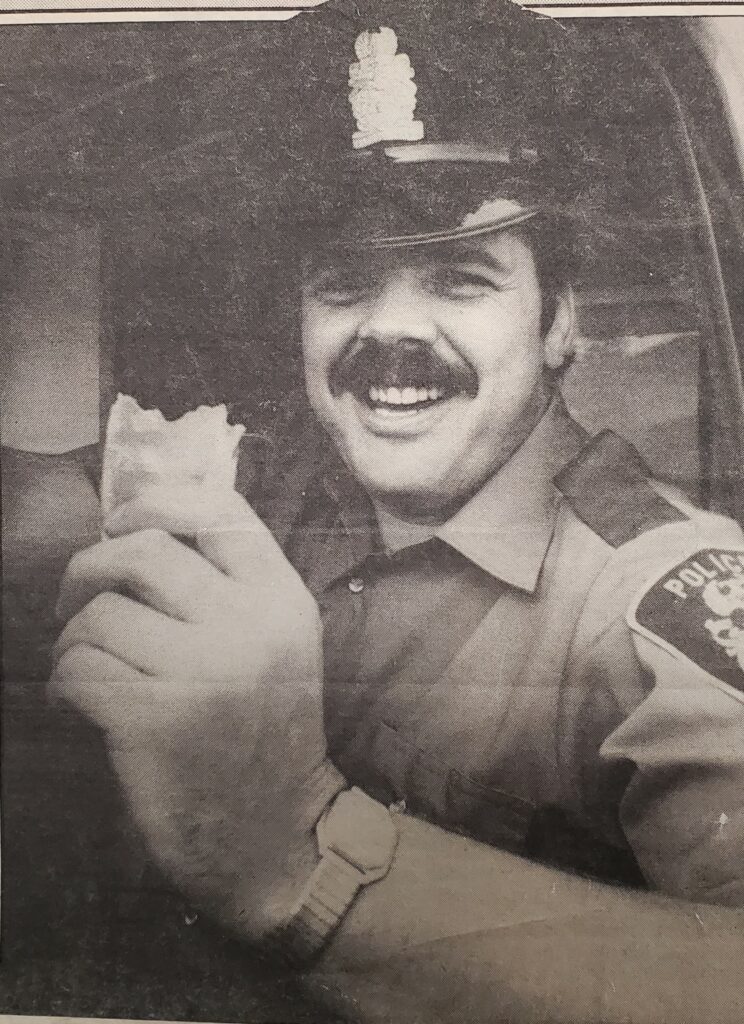

We can see a lot of the actions taken by the Matsqui police through the ASM News as well as the various police files and records in the Reach. A news report was done on the good the police force has done, including a section on their school visits. The article describes how the police went to schools to lecture about traffic safety, as well as talked to groups like the Boy Scouts.4 Their purpose behind this kind of outreach is that “on many occasions it’s possible to prevent things before they actually occur.”5

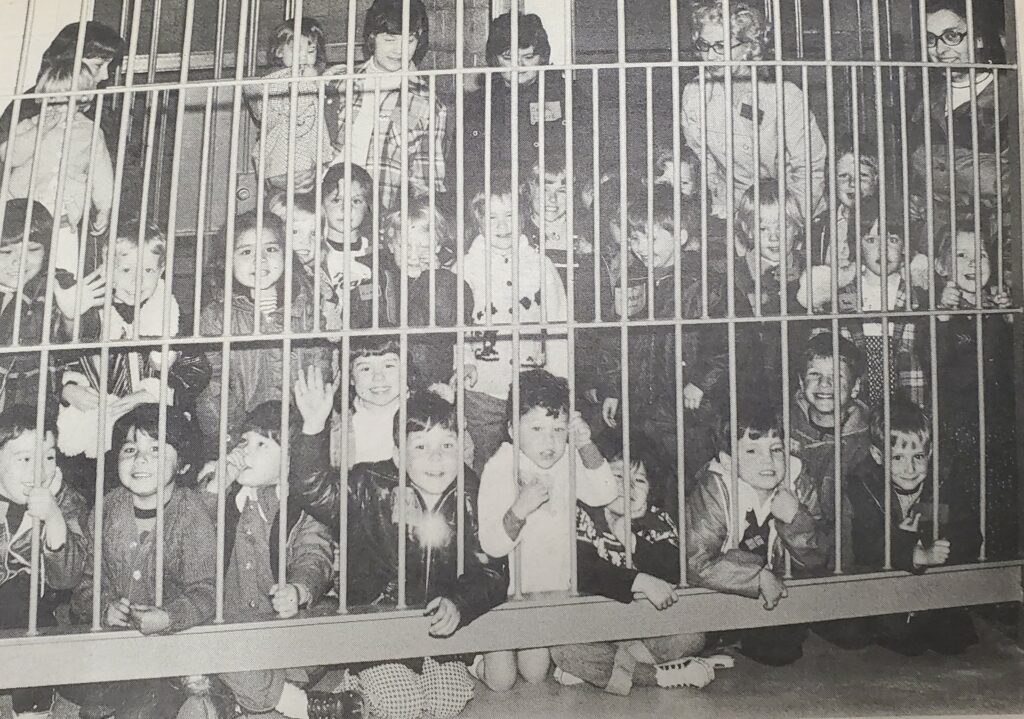

We see similar actions taken in the 1980s as in an issue of the ASM News, dedicated to the anniversary of the Matsqui police, they also discuss school patrols and visits to the station on field trips.6 In 1982 the police also reported having stepped up their attempt to prevent crime through outreach with children. This outreach involved reaching out to schoolchildren to teach the difference between acceptable and unacceptable behaviour and to familiarize student with the police and their duties.7 Chief Jim Stuart stated that this was not an attempt to replace teachers and parents, but rather “adding on to the effect” those groups have on children before they reach the stage of juvenile delinquency.8

In the same issue of the paper dedicated to the police, an open letter signed by “The cop down the street” is made out to parents.9 The cop details a grizzly scene of a car crash, including a girl who will be in a wheelchair for her life, the driver who will forever bear the scars of the incident, and the horror he felt as a first responder.10 This cop is particularly incensed by teenage alcohol consumption, stating that at the scene of the accident he “would give anything to know who furnished those young people with that booze.”11

The cop goes on to blame the parents, stating that this accident happened because “you as parents weren’t concerned enough about your child to know where he was and what he was doing; and you were unconcerned about minors and alcohol abuse and would rather blame me for harassing them when I was only trying to prevent this kind of tragedy.”12 This cop laments that he is made the ’bad guy’ for having to be the bearer of horrible news and warns that if parents do not take his words seriously, they will find him “at your doorstep, eyes downcast, staring at my feet, with a message of death for you.”13

So, we can see the police being concerned about traffic safety and alcohol abuse, but what do we see in their official reports? In a 1981 community meeting, the police discussed their juvenile crime prevention program, which included “community crime prevention committees … youth and family counselling, and … school liaison programs.”14 They state that they are seeking funding to reduce the number of young people entering the criminal justice system, help communities overcome the fear of crime and delinquency, and solve several problems including vandalism, theft, juvenile gangs, drug and alcohol abuse, and suicides.15 They list several possible solutions, including community shelters for adolescents, school programs for “kids turned off school,” youth programs – educational and leisure, as well as a number of programs dedicated to parenting and police support.16

Throughout these sources we can see that attempts were made by the Matsqui Police to reach out to and help adolescences to prevent delinquency. However, not all cops seemed to worry as much about the safety of the youth.

Protect and Serve? – Police Brutality Allegations and Distrust of the Police

The Matsqui police are not free from their share of criminal allegations. In 1981 an internal investigation was launched into allegations that policemen had used excessive force in breaking up a teenager’s graduation beer party.17 The paper also states that they have received several complaints from teenagers who alleged that “police smashed car windows with billy clubs and beat youths with flashlights.”18 The results of this investigation were not included in this article, but the fact that so many people had stories of youths being abused by the police is notable even without the internal investigation’s results. While we see the police trying to reach out to the youth and help them, we also see cases like this which can easily result in many teenagers distrusting the cops.

Youth are already likely to distrust the police before even adding cases like this one into the mix. A large aspect of delinquency is a lack of respect for authority, and who represents authority better than the boys in blue? Historian Owen D. Carrigan states that by the early 1990s the youth in Canada were more hostile towards the police than they had been in decades past, frequently verbally and physically assaulting police officers.19 Combine this mentality with news reports of police officers assaulting teens and you have a situation where distrust would be prominent. Unfortunately, there are no statistics or news stories to back this claim up, only assumptions based off of nationwide research and events that happened in our area.

Conclusions

Rather that the inactive idea Tanner gives us of Canadian police, we can see that within Matsqui the police were actively engaged in preventative measures to keep teenagers healthy, safe, and out of crime. Serious attempts seem to have been made to prevent many of the crimes and tragedies we see in other sections of this website. However, this does not erase the fact that many teenagers reported police violence, and likely heavily distrusted the officers in their schools and broader communities. This mentality would likely add even more to the stigma of reporting crimes and could have even undone some of the work the police did with outreach programs.

Whether or not these efforts worked would take a deep analysis of statistics I unfortunately did not have access to, so we can only make assumptions based off the good and the bad effects the police had on the youth of the Fraser Valley.

Endnotes

1 Julian Tanner, Teenage Troubles: Youth and Deviance in Canada (Ontario, Oxford University Press, 2015), 135-6.

2 Tanner, Teenage Troubles, 262.

3 Tanner, Teenage Troubles, 263.

4 “One way to judge good police work – all the things that never happened,” Jan. 28, 1970, news clipping, in Law Enforcement Box, folder Community Services/ Law Enforcement/ Municipal Police, The Reach Archive, Abbotsford, B.C.

5 “One way to judge good police work – all the things that never happened.”

6 “Police co-ordinate Matsqui school patrols,” ASM News, July 30, 1980.

7 “Matsqui Police look back on the best and the worst of ’82,” ASM News, April 27, 1983.

8 “Matsqui Police look back on the best and the worst of ’82,” ASM News, April 27, 1983.

9 “Open letter to parents,” ASM News, July 30, 1980.

10 “Open letter to parents,” ASM News, July 30, 1980.

11 “Open letter to parents,” ASM News, July 30, 1980.

12 “Open letter to parents,” ASM News, July 30, 1980.

13 “Open letter to parents,” ASM News, July 30, 1980.

14 “Abbotsford-Clearbrook Chamber of Commerce Meeting Briefing,” April 27, 1981, in Law Enforcement Box, folder Community Services/ Law Enforcement/ Municipal Police, The Reach Archive, Abbotsford, B.C.

15 “Abbotsford-Clearbrook Chamber of Commerce Meeting Briefing.”

16 “Abbotsford-Clearbrook Chamber of Commerce Meeting Briefing.”

17 “Police investigate brutality allegations,” ASM News, June 17, 1981.

18 “Police investigate brutality allegations,” ASM News, June 17, 1981.

19 Owen D. Carrigan Juvenile Delinquency in Canada: A History (Concord: Irwin Pub., 1995), 202.