Introduction

This page will go over the crimes committed against teenagers, both in Canada broadly for some background information, and then will look specifically at the Fraser Valley. We will specifically look at how academic sources view teenage victims, how the news portrays them, and analyse if there are any trends in how these crimes are reported on in Canada broadly and in the Fraser Valley more specifically. The page “Crimes by Teenagers” will then look into teenage criminals as a counterpart to this one.

Background Info – The ‘Dark Figure of Crime’

One crucial thing to note before discussing teenage victims is how and why teenagers do or do not report crimes. The crimes that we hear about in police reports and the newspapers are what is known as “crimes known to the police,” however, “the official count of crime includes only a small proportion of illicit behaviour that actually takes place.”1 The police are heavily reliant on the public reporting crimes to them, as an American study from 1970 found that officers only detect about 10% of crime.2 That remaining 90% is what people report in. However, there is what is known as “the dark figure of crime,” that is all the crimes that go unreported, and it is usually a very large number.3

Adolescents have been found to be far less likely to report violent victimization than adults are, especially if these crimes occur in places that are considered “off limits” by authority figures such as their parents, or if they feel they will be shamed by peers for being a “snitch.”4 Along with this comes the harrowing truth that “individuals between the ages of 15 and 25 are at greater risk of violent victimization than any other age group” with sexual assault being a crime predominantly targeted at young women and girls.5

Not all of these crimes are done by adults though, as often “those who perpetrate violence against young people are often other young people” adding to the stigma against teenagers as dangerous and adding to the peer pressure to not report.6 With this in mind, we can only turn to the reported crimes as evidence as unreported crimes are, by definition, undocumented, and only exist in oral histories and personal testimonies, neither of which are deemed newsworthy. So, operating with the knowledge that these documented crimes are only a fraction of the whole truth, we can turn to what the police did know about.

Unnamed Victims

Trigger Warning: Sexual Assault & Rape

Throughout the papers there is one interesting aspect of reporting that separates teenage victims into two categories, those who are named and those who are not. A 1986 article discusses Ronald Wayne Jensen who assaulted a seventeen-year-old prostitute as well as kept a sixteen-year-old captive and sexually assaulted her.7 Obviously these girls were unnamed because at the time the article was released, they were living victims of horrible crimes and it was for their safety and privacy to not reveal any identifiable details. Another victim of rape, a fifteen-year-old from Matsqui was also unnamed in an article detailing a 30-month sentence for her rapist, Andrew Harry Brooks.8

Keeping victims of sex crimes anonymous seems to be a common practice regardless of age, as we also see examples such as a Chilliwack twenty-year-old woman remaining unnamed and unidentified in the papers.9 We can also see how these sorts of traumatic incidents stay with the victims as in a Dear Abby column in The Chilliwack Progress we see a middle-aged woman asking for advice for what she should say when people ask about a knife scar she got when she was raped as a teenager.10 She states that “very few people know about the rape. [She] never reported it to the police, although now [she wishes she] had.”11 One thing to note is that this whole Dear Abby section is headlined “Rape victim carries physical as well as emotional scar” despite there being a half dozen questions answered by Abby.12 This woman’s trauma became a headline when she only wanted anonymous advice.

Headstones and Headlines

Trigger Warning: Assault & Murder

When teenage victims are named, it is often because they are dead. Two specific cases will be used as examples here, namely the murder of Deborah Faye Zimmer and the shooting of four Chilliwack teens: Evert den Hertog, Bert Menger, Jan den Hertog, and Leola Guliker. These two cases were heavily discussed in the ASM News and The Chilliwack Progress. Laying out the entire history of the reporting on these cases seems unnecessary, so instead I will detail what happened, and who was accused/charged then we will examine what the focus on these teenagers’ deaths tells us.

Zimmer

Deborah Faye Zimmer was shot to death on her seventeenth birthday in 1985. Three men were charged, Thomas Patrick Owens for assault causing bodily harm and possession of a weapon for a purpose dangerous to the public peace, Lew Kirkby for an assault and weapon conviction, and Larry Zimmer, her brother, for a beating that occurred before the shooting.13 This case was dramatized in the news, as an account of the trial reads like a true crime book. Leita McIntosh writes about a confrontation after chasing a sportscar as such:

Once up the driveway, Kirkby said he was approached by a man, whom he struck to the ground. "I hit him open-handed, and said 'What the f---'s the problem?' On his way up he said, 'There's no problem, there's no hassles." Realizing the man "didn't want to fight," Kirkby said he went to break Larry Zimmer away from a separate battle that was ensuing inside the sportscar. Seconds later, Kirkby said a man approached carrying a rifle and said, "Do you guys wanna f--- around? Do you wanna play rough?" The witness said a shot rang out, he ducked for a moment, and then ran down the driveway. After hearing another shot behind him. Kirkby said he turned back up the driveway and found his Camaro -- with Larry, Deborah, and Denean inside. "Larry was screaming, 'Debbie's been shot! Debbie's been shot!'" he said. Meanwhile, Denean Barkman was in the back seat, a gunshot wound in her hand. Kirky told the court he jumped into the car and sped away to the hospital.14

McIntosh continues by describing Deborah Zimmer’s last moments: ““Don’t shoot us! We’re girls!” Those may have been the last words Deborah Zimmer said before a shotgun blast killed her on her 17th birthday.”15

This account does give a look into what the court case was, but it also feels like a spectacle. The readers of the paper are not the jury members whom these accounts were meant for, and in retelling them as this story of road rage, a driveway brawl, and finally the tragic death of a teenage girl it feels meant to entertain. McIntosh patches together separate witness statements to create a narrative for her readers to discuss over cereal and coffee, not unlike a true crime youtuber discussing murders while she does her makeup.

This is not the only case of Zimmer’s death being used like this though, as on the front page of the ASM News, her mother is interviewed after Larry Zimmer’s sentence. She says, “It’s so unjust… Why couldn’t Larry or Lew get a suspended sentence? Or a fine? … First we lose a daughter, now we lose a son.”16 The wording includes descriptors such as “distraught mother” and starts with the line: “To his family, it seemed like the ultimate irony” as a way of pulling readers in with curiosity and sympathy.17 There is drama in this story; twists and turns and dramatic irony that you will only get from your friendly local paper, so make sure you keep buying it!

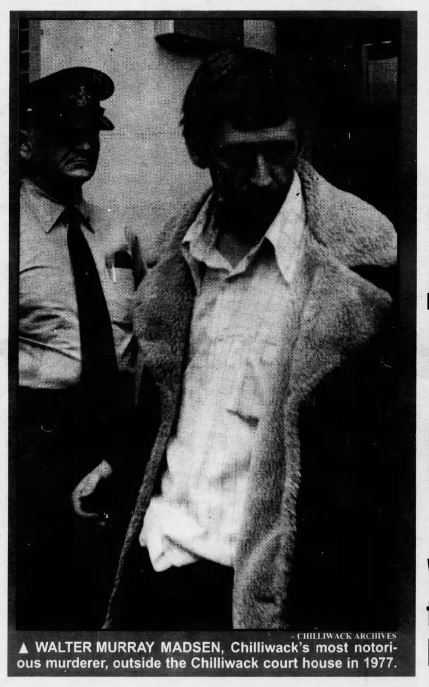

The ‘Rosedale Murderer’

The shooting of the Chilliwack teens is much the same story of dramatization. This one focuses much more on the killer than the victims, however. Walter Murray Madsen was charged with four counts of first-degree murder and given a life sentence.18 The biggest question the jury faced was if he was insane or not, which would drastically alter the charges placed on him, and almost all the reporting done focusses on his mental state.19 Considering the time when this case was publicized may shed some light on why the killer was the centre of attention. Think about the serial killers active in the late 1970s: Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, Jeffrey Dahmer, David Berkowitz, and so many others that now live in our cultural zeitgeist.20 It makes sense that a local paper would jump at the chance to join in on the conversation of the psychology of a killer.

The way they describe Madsen feels so similar to the ways we discuss America’s serial killers. For instance, this exchange was written about between Madsen’s lawyer, Young, and Dr. John Duffy, a forensic psychiatrist:

In response again to a question by defence counsel, Dr. Duffy pointed out "This man (Madsen) is not mentally ill; (although) I did not say he was perfectly normal." Madsen's lawyer then asked "The raison d'etre was because he was bored?" "Yes," said Duffy. "Could he kill four people because he was bored?" questioned Young. "Yes," said Duffy.21

They also describe his plans as “chess pieces and pawns – his only emotion was when he made a plea not to return to prison because people treated him poorly there.”22 These quotes feel right out of a Netflix documentary to me.

When the victims are talked about it is about the recovery of their bodies, such as Leola Guliker’s body being found in the water near UBC. The family is quoted as expressing relief about finding her body and the paper includes a discussion about the reason she went undiscovered so long being due to stages of decomposition.23

The family of the one surviving teenager, fifteen-year-old Ed Menger, are also interviewed, recalling how they cried when Ed was brought home alive by the police.24 Interestingly, this article does touch on Vancouver reporters who allegedly took the story and exaggerated details. On receiving phone calls from reporters, Mr. Menger states: “Sometimes the reporters phoning up would even say, “I loathe my job,” he said, and “I felt sorry for the guys since it was their job.” At the same time, he admitted, without the press keeping the story in public light, the tips may not have come in. “It is not a necessary evil, but a necessary tool, in helping to find this guy,” said Mr. Menger.”25

Getting the opinion of someone directly affected by reporting is fascinating, as we see that the Mengers did not like the attention, but felt it was necessary to bring their son’s killer to justice. However, the fact remains that this story made for an interesting read, and Madsen hanging himself in 1996 made the front page of the paper along with his title of the Rosedale Murderer.26

Conclusions

The news obviously used cases like these to sell papers and get attention, but as we can see from Menger’s words there is good that comes with this kind of morbid voyeurism we get as consumers of news. Some level of protection is offered to victims of very personal and traumatic crimes, but as soon as they are dead, regardless of age the news is free to use their names and stories to sell. In the same way True Crime podcasts, documentaries, and books exist to sell horror as entertainment, these cases were used to sell papers.

The exploitation of the dead for money is a tough ethical question. On one hand, the news helped the Mengers find justice, but on the other we see the Zimmer family’s trauma laid out plainly for our viewing enjoyment. Digging deeply into the ethics and morals of consumerism and capitalism in the news is far beyond what I set out to do with this website. Likewise, considering the time frame being discussed, I’d rather not be labelled a Communist for delving into that discussion.

Endnotes

1 Julian Tanner, Teenage Troubles: Youth and Deviance in Canada (Ontario, Oxford University Press, 2015), 42-3.

2 Tanner, Teenage Troubles, 43.

3 Tanner, Teenage Troubles, 43.

Tanner, Teenage Troubles, 44.

5 Tanner, Teenage Troubles, 51.

6 Tanner, Teenage Troubles, 52.

7 “One year jail sentence for attack on prostitute,” ASM News, Feb. 5, 1986.

8 “30 months for rapist,” ASM News, April 30, 1988.

9 “Conviction on attempted rape,” Chilliwack Progress, Oct. 24, 1979, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/77123181/?terms=victim&match=1.

10 “Rape victim carries physical as well as emotional scar,” Chilliwack Progress, Nov. 18, 1989, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/81439230/?terms=%22rape%20victim%20carries%20physical%20as%20well%20as%20emotional%22&match=1.

11 “Rape victim carries physical as well as emotional scar,” Chilliwack Progress, Nov. 18, 1989, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/81439230/?terms=%22rape%20victim%20carries%20physical%20as%20well%20as%20emotional%22&match=1.

12 “Rape victim carries physical as well as emotional scar,” Chilliwack Progress, Nov. 18, 1989, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/81439230/?terms=%22rape%20victim%20carries%20physical%20as%20well%20as%20emotional%22&match=1.

13 “Jail term for beaing before sister shot,” ASM News, March 5, 1986.

14 Leita McIntosh, “Trial probes birthday death”, Chilliwack Progress, Nov. 6, 1985, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/80581645/?terms=zimmer&match=1.

15 Leita McIntosh, “Trial probes birthday death”, Chilliwack Progress, Nov. 6, 1985, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/80581645/?terms=zimmer&match=1.

16 “Jail term for beating before sister shot,” ASM News, March 5, 1986.

17 “Jail term for beating before sister shot,” ASM News, March 5, 1986.

18 “‘Life; sentence for teen murders”, Chilliwack Progress, April 19, 1978, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/77137380/?terms=life%20sentence&match=1.

19 “Madsen interviews described in Thursday, Friday sessions”, Chilliwack Progress, April 19, 1978, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/77137495/.

20 Eric W. Hickey, Encyclopedia of Murder & Violent Crime (London: SAGE Publications, 2003): Appendix 2: Serial Killers.

21 “Madsen interviews described in Thursday, Friday sessions”, Chilliwack Progress, April 19, 1978, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/77137495/.

22 “Madsen interviews described in Thursday, Friday sessions”, Chilliwack Progress, April 19, 1978, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/77137495/.

23 “Leola buried today,” Chilliwack Progress, April 26, 1978, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/77137646/?terms=madsen&match=1.

24 “Victim’s parents tell of ‘sense of relief’,” Chilliwack Progress, Sep. 7, 1977, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/77093587/?terms=%22I%20felt%20sorry%20for%20the%20guys%22.

25 “Victim’s parents tell of ‘sense of relief’,” Chilliwack Progress, Sep. 7, 1977, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/77093587/?terms=%22I%20felt%20sorry%20for%20the%20guys%22.

26 “Rosedale murderer takes own life,” Chilliwack Progress, June 28, 1996, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/80932708/?terms=madsen&match=1.