Introduction

This page will go over the crimes committed by teenagers, both in Canada broadly for some background information, and then will look specifically at the Fraser Valley. We will specifically look at how academic sources view teenage crimes, how the news portrays them, and analyse if there was a moral panic about teenage criminals in Canada broadly and in the Fraser Valley more specifically. The page “Crimes on Teenagers” will then look into teenage victims as a counterpart to this one.

Background – The Young Offenders Act

Before discussing teenage criminality, an important act needs to be explained. In 1985 the Canadian Government brought the Young Offenders Act into law which set the standard for who would be considered a child, young person, or adult under the law. A child is defined as someone under the age of twelve, and a young person is between twelve and eighteen1. Before 1985 the age a person was considered an adult in the court was seventeen in B.C.2

What stands out most with this change in legality in the papers is how juveniles are discussed. In a 1987 ASM News article about a seventeen-year-old charged with attempted murder and auto theft, the news states that “juveniles charged under the Young Offenders’ Act may not be identified, nor may circumstances be published which could identify the accused.”3 Before 1985 anyone seventeen or older was named and identified just like an adult. For instance, in a report on a narcotics arrest, the paper names “Brian J. Knights 20, Michael David Laframbrose 18, Manda Toth, 17, and a local juvenile.”4 This makes it a little tricky to discuss much about the ways juvenile criminals were treated by the news post 1985 as there are far less details, but what is there is interesting.

Troublesome and Troubling

Sociologist Jennifer Silcox writes that “when youth are shown in news representations, they are more often depicted as perpetrators of crime, rather than as victims or actor.”5 Sociologist Julian Tanner likewise states that youth are “both “troubling” and “troubled”” in our social understanding.6 We will investigate the victimhood of teenagers in a different section of this website, but here we will examine juvenile criminals and their crimes.

The most complete statistics we have come from a 1979 Matsqui Police Annual Report where a breakdown of crimes done by adults and juveniles is reported. Remember that at this time, a juvenile was anyone sixteen or under. Here is a chart simplifying the results of that report and focusing on ones that are relevant to teenage crimes (i.e., excluding immigrations and customs offenses which no juveniles committed, and homicide of which there were no charges in 1979):7

| Crime by Category | Adults Charged | Juveniles Charged |

| Sexual Offenses (Rape, Indecent Exposure, etc.) | 12 Male, 0 Female | 2 Male, 0 Female |

| Assaults (Both by Civilians and Police) | 46 Male, 3 Female | 3 Male, 0 Female |

| Robbery (With and Without Weapons) | 3 Male, 4 Female | 5 Male, 0 Female |

| Property Crimes (B&E, Vehicle Theft, Fraud, etc.) | 160 Male, 56 Female | 137 Male, 42 Female |

| Drug Possession & Trafficking | 52 Male, 1 Female | 3 Male, 0 Female* |

| Liquor Act | 46 Male, 2 Female | 9 Male, 5 Female |

| Other (Arson, Kidnapping, Trespassing, etc.) | 78 Male, 5 Female | 37 Male, 2 Female |

What stands out the most in this report is how similar property crimes and robbery are between adults and juveniles. While all other crimes are much lower for juveniles, these two are at comparable levels. Looking at census data, in 1981 Matsqui had a population of:

| Total: | 42,001 |

| 10-14 Years Old: | 3,570 |

| 15-19 Years Old: | 3,745 |

| 20+ Years Old: | 29,712 |

Considering the stats for the police report come only two years prior we can assume these numbers were similar in 1979 which makes the number of juvenile offenders under the robbery and property crimes sections very startling. Obviously since the data we have lumps the ages of 15-19 together, the actual number of juveniles is different, but considering the 10-14-year-old population is a similar number we can assume that the 12-16 age range is within a similar range to use the 15-19 statistics as a basis for comparing the Matsqui Police’s stats to the number of juveniles in the area. We cannot know if any of these charges came from repeat offenders unfortunately, but if none are that is about 5% of the 1981 15-19-year-old population and less than 1% of the adult population who were charged with robbery or property crimes. This suggests that far more teenagers, proportionately, were taking part in these kinds of property crimes than adults did.

Another interesting note is the gender divide in these crimes. Far less women, both adult and juvenile, committed crimes. Current research suggests that girls and women are far less likely to become involved with crime.8 Additionally, the kinds of crimes juvenile girls are likely to commit were not tracked by the Matsqui report, namely running away from home, loitering, and, most notably, prostitution.9 Therefore, most of the crimes we will discuss were committed by men and juvenile boys.

Our Thieves and Vandals

Looking at the numbers, property crimes were the most numerous and we can see that corroborated by the news. Editions of the ASM News in 1979 had a section dedicated to the Matsqui Police Blotter and RCMP report which informed the public about minor crimes such as: “Three Abbotsford juveniles were arrested and charged with shoplifting on April 12” and “Report of youths throwing beer bottles from a vehicle in the parking lot of a theatre on McCallum Road.”10 Now these crimes are obviously quite minor and so only receive minor attention in the paper, however it is important to remember that the statistics tell us that despite how minor they appear in reporting, these kinds of crimes were the ones teenagers were committing most often.

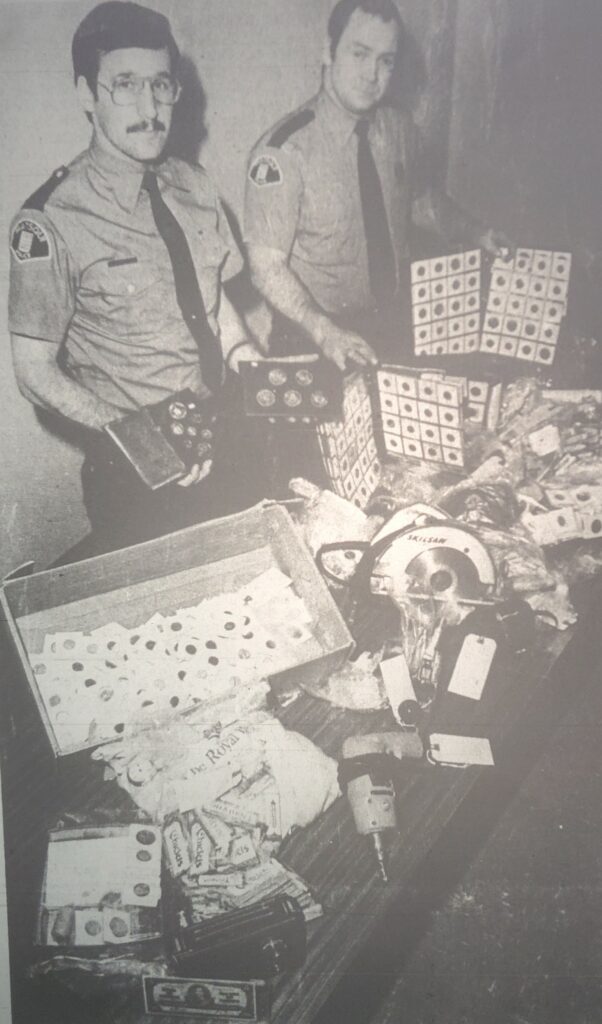

One example of a theft that got far more attention was on February 9, 1979, where three juveniles were arrested, and the police recovered $4,500 worth of stolen goods as seen to the left.11

By the mid eighties however, we begin to see a moral panic about teenage property crimes. Silcox describes how we can see a moral panic about the youth through “the exaggerated focus on stereotypical and inaccurate portrayals of young people and their involvement with ‘deviant’ behaviour.”12 In a news article titled “’Just kids’, but they do 80% of breaks and enters” Matsqui Police Constable John Skorupa is quoted saying “80 percent of all our work is done by the kids – youngsters under age 18.”13 This article continues on to give advice about securing your property and taking walks around the neighbourhood to get to know what is normal.

The most striking thing when debating if there is an air of moral panic to this though, is two textboxes dropped in the middle of the article giving statistics. We see statistics such as “In Abbotsford, there were 374 cases of break, enter and theft in 1984 and 419 the following year” and the one featured above with caricature of a cartoony thief and more worrying statistics.14 A large section of a lifestyle page is dedicated to these preventative tips, something that would make anyone worried about the safety of their neighbourhood, and all of it is framed with the idea that a teenager will be the one committing the crime.

While further Matsqui Police Reports exist, they do not break down the crimes by juveniles and adults, but we can see this chart in their 1983 report which shows a growing number of B&E reports.15 The statistics given in the “Just Kids” article states that Matsqui had more that 17,000 calls for police in 1984, and over 22,000 in 1985.16 This shows an upward trend which explains why there would be a panic about crime, but why teenagers?

Unfortunately, we can only speculate based on the 1979 statistics on how many of those B&Es were committed by juveniles or take the word of Constable Skorupa that it is 80%. We can assume he is speculating that number as the article states: “when police talk to residents, they find the home had been broken into but the incident was not reported because the residents “thought it was just kids”.”17 Nonetheless, this shows a panic about the number of B&Es occurring even if many residents brush them off as just kids being kids. It is possible that the police and news were overexaggerating the issue to get people to better secure their homes, or perhaps there really was an epidemic of the youth sneaking into unlocked houses.

Our Violent Delinquents

Trigger Warning: Assault & Murder

According to Historian Owen D. Carrigan there has been a trend since the 1980s of juveniles committing more violent crimes and showing an indifference to the morality of their actions.18 He goes on to cite a number of cases from the 1980s of young people committing violent crimes such as murderer as young as age twelve.19 However he does note that “while the annual number of murders committed by teenagers is not large relative to the juvenile population, they are symptomatic of the growing trend to random violence.”20

Before we can take Carrigan’s word as the be-all-end-all though it is important to note that his sources for this assertion are the same as what we will look at: the news.21 This brings us back to the idea of moral panic, something much more insidious in this case than it was with teenage B&E. A review of the Toronto Star found that the incidents reported in a week of newspapers were not petty thefts of candy bars or the breaking and entering of residential homes, but rather “spectacular but atypical crimes of violence such as drive-by shootings.”22

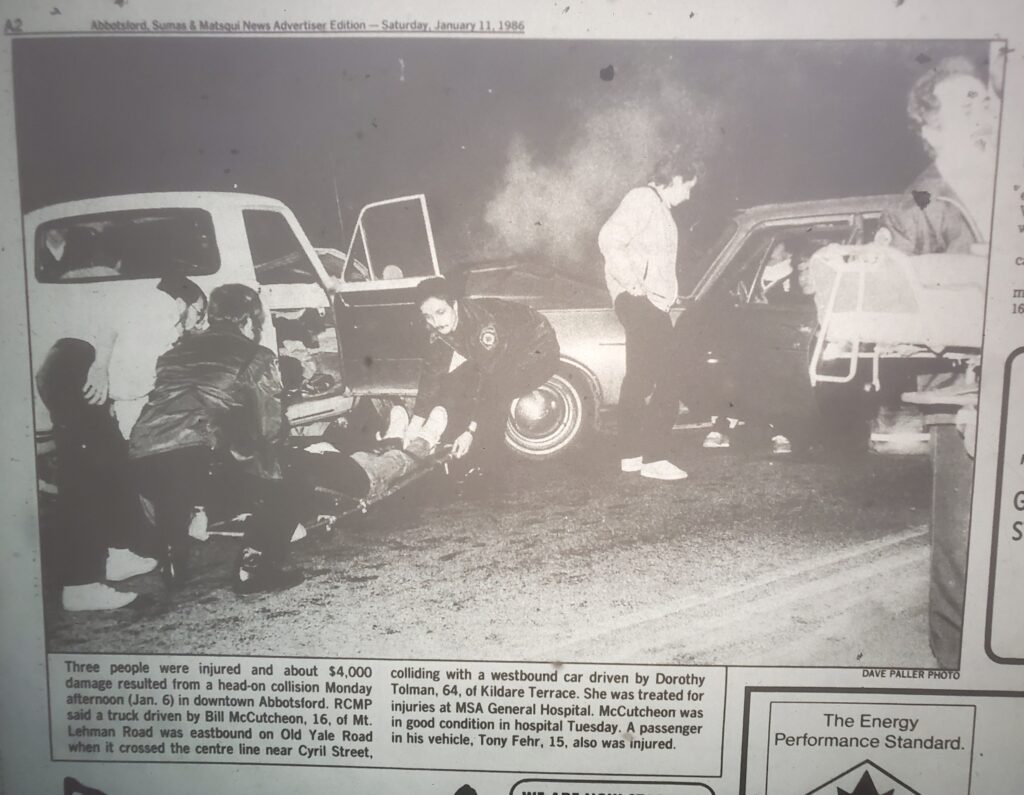

So, what about our local news? One thing that is immediately apparent in how the news framed violent stories is that crimes are often on the first few pages of the paper, the place where you would want to put the stories that draw people in. such as this example which featured on the second page of a paper:

However, the moral panic we see with B&E seems missing from the reports of violent crime. For example, one report from 1987 reads as such: “An Abbotsford youth has been charged by the RCMP with attempted murder of his father. The male, 17, was also charged with theft over $1,000. He was arrested at the family home … the youth’s father was not seriously injured.”23 Other reports are much the same, laying out the attempted murder and theft as well as noting that circumstances could not be published due to the Young Offenders’ Act.24 Now this case unfortunately does not tell us much past the bare facts, but there is a different case which got a more colourfully article written.

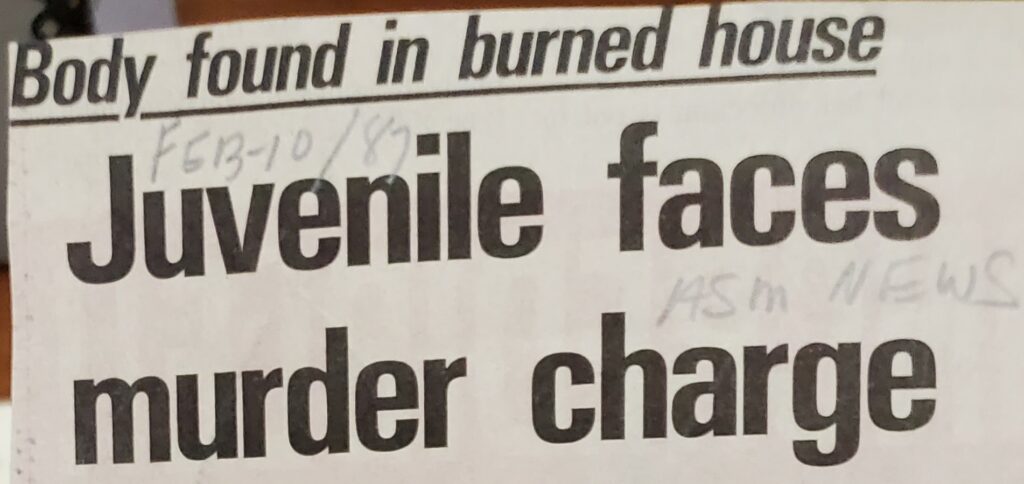

In 1989 a seventeen-year-old was charged with second-degree murder after the body of an adult male was found in a burned house. While little information is given about the culprit, we do get far more details here than in the previous example, such as that the youth was already known to the police, that the man died of a gunshot wound before being left to burn in the home, and that it would be determined later if the teenager committed pre-meditated murder or not.25 This teenager was described in very non-inflammatory ways as we are told he “has a history of petty crime” and is referred to as a youth, teenager, and juvenile.26

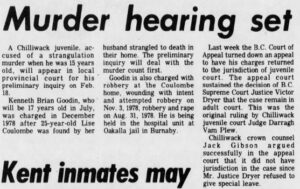

Another case comes from Chilliwack where the teenager was tried in provincial court rather than juvenile court and was therefore named. Fifteen-year-old Kenneth Brian Goodin was tried for second degree murder after allegedly strangling Lise Coulombe in her home.27 It is interesting to note that we get Goodin’s name despite him being a juvenile, likely because he was tried as an adult. Goodin would receive a life sentence in 1981 after his case was moved to a New Westminster court. Goodin was deemed mentally ill, but a psychiatrist stated that “despite the accused’s youth, given the prognosis here, the court has no choice” but to give a life sentence.28

Compare the way these teenagers are discussed to what we see in the investigation of Deborah Zimmer’s death, which will be looked at more closely in the Crimes on Teenagers section. In discussions of the Zimmer shooting, we see word choices like the suspects being “bent on mayhem, bent on destruction.”29 While there are articles that go over only the facts, we still see language like this that does not appear in either of these juvenile cases.

Adding Race into the Mix

Trigger Warning: Murder & Racism

One case stands out, the murder of Ranjit Toore. One thing anyone who has spent time in the Fraser Valley will know is that there is a large South Asian population in the 21st Century. The Sikh population has been in the area for a long time, as evidenced by buildings like the Gur Sikh Temple, which makes the lack of Indian names interesting to discuss.

There is some research done already that can explain this lack of Indian criminals. Tanner states that immigrants do not commit more crimes than long-time citizens, and in fact, tend to commit far less crimes on average.30 When looking at immigrant youth we see a similar story. Tanner states that research shows that the strong bonds between immigrant youth and their parents, as well as the desire to not jeopardise their, and their parents’, aspirations for higher education and good careers, leads to far less delinquent activity.31

Important to the discussion of this Matsqui murder case, Tanner even points out that among immigrant groups, “the group most distinctive in terms of their non-delinquent lifestyle is South Asian youth.”32 Whether South Asian family values or religions play into this goes beyond the scope of this website, and beyond my own limited knowledge of Indian religions, but the facts remain that South Asians are distinctively non-delinquent.

So, what happened in the Toore murder? Ranjit Toore was found dead in her home by firefighters after a house fire was put out. Her husband, Jagraj Singh Toore and eighteen-year-old Satpal Singh Jhatoo were initially tried for her murder.33 Later, Toore would be charged as well as an unnamed juvenile with first-degree murder.34 It must be noted that the lack of identifiable details in the other youth murder cases do lead to a racial ambiguity on whether they were white or not, but since we cannot say for sure, this stands as the only example in the Reach’s murders folder of a, presumably, Indian teenager committing murder.

The brushing off of race being an issue is an interesting one as we only have Mouat’s word to go off of that these students just happened to be in race segregated groups that fought. I would like to turn to Desmond Cole, a Canadian journalist who gives an interesting perspective that proves useful here: “White supremacy encourages the people it benefits to create their own parallel universe, their own set of facts and explanations about the existence and prevalence of racism. Even as white people insist that “no one really knows what happened,” they can immediately share an explanation that eases their anxiety and shame.”37 In brushing off this incident as merely a lack of sportsmanship, it erases the racial aspect at play in this case of delinquent activity.

Conclusions

This leads to an interesting conclusion, that unlike the fearful image Carrigan would have us believe, in Abbotsford, Sumas, and Matsqui, there was not an epidemic of teenage psychopaths murdering indiscriminately. The fact that these crimes were mostly familial, or at least between people who know each other somewhat well (such as neighbours), discredits the random aspect that Carrigan saw nationwide. Likewise, the small number of cases (at least within the Reach’s archive) tells us that the area was either atypical, or there was a moral panic nationwide that we cannot see corroborated within our local history.

Meanwhile when it comes to race, we are unfortunately working with little to go off of. As Tanner explains, many immigrants are unlikely to commit crimes and in discussions of youth it becomes even trickier as the need to protect minors’ identities leads to an obfuscation of racial crimes in the papers. Were any of these teens Indian? We unfortunately cannot know and therefore cannot comment on if the Toore case was an interesting outlier or emblematic of a larger trend.

Endnotes

1 Young Offenders Act, (1985), https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/y-1/20030101/P1TT3xt3.html

2 Julian Tanner, Teenage Troubles: Youth and Deviance in Canada (Ontario, Oxford University Press, 2015), 243

3 “Youth charged with attempted murder”, ASM News, Jan. 21, 1987.

4 “Eighteen arrested in narcotics sweep”, ASM News, March 14, 1979.

5 Jennifer Silcox. “Youth crime and depictions of youth crime in Canada: Are news depictions purely moral panic?” Canadian Review of Sociology 59, no. 1 (February 2022): 100.

6 Tanner, Teenage Troubles, 27.

7 “Matsqui Police Service 1979 Annual Report,” in Law Enforcement Box, folder Community Services/Law Enforcement/Municipal Police, The Reach Archive, Abbotsford B.C.

8 Tanner, Teenage Troubles, 205.

9 Tanner, Teenage Troubles, 205.

10 “Matsqui Police Blotter”, ASM News, April 18, 1979 & “RCMP Report”, ASM News, Jan. 24, 1979.

11 “Stolen property recovered”, ASM News, Feb. 9 1979.

12 Silcox, “Youth crime,” 99.

13 “‘Just kids’, but they do 80% of break and enters”, ASM News, Feb. 12, 1986.

14 “Prevention of break-ins”, ASM News, Feb. 12, 1986.

15 “Matsqui Police Report.”

16 “‘Just kids’, but they do 80% of break and enters”, ASM News, Feb. 12, 1986.

17 “Prevention of break-ins”, ASM News, Feb. 12, 1986.

18 Owen D. Carrigan Juvenile Delinquency in Canada: A History (Concord: Irwin Pub., 1995), 177.

19 Carrigan, Juvenile Delinquency, 178.

20 Carrigan, Juvenile Delinquency, 178.

21 Carrigan, Juvenile Delinquency, 214.

22 Tanner, Teenage Troubles, 7.

23 “Son Charged for Murder Attempt”, Abbotsford/Mission Times, Jan. 21, 1987.

24 “Youth charged with attempted murder”, ASM News, Jan. 21, 1987.

25 “Juvenile faces murder charge”, ASM News, Feb 10, 1989.

26 “Juvenile faces murder charge”, ASM News, Feb 10, 1989.

27 “Murder hearing set”, Chilliwack Progress, Jan. 16, 1980. https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/77119633/?terms=goodin&match=1.

28 “Mentally ill 17-year-old gets life for killing woman”, Vancouver Sun, April 15, 1981, https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/april-15-1981-page-3-96/docview/2241075647/se-2.

29 “Two families torn by manslaughter verdict”, ASM News, Nov. 20, 1985.

30 Tanner, Teenage Troubles,109.

31 Tanner, Teenage Troubles, 109.

32 Tanner, Teenage Troubles, 110.

33 “Murder suspects go to trial”, ASM News, May 7, 1986.

34 “Juvenile is charged in murder”, ASM News, Dec. 18, 1986.

35 “Brawl not racially motivated”, ASM News, March 28, 1987.

36 “Brawl not racially motivated”, ASM News, March 28, 1987.

37 Desmond Cole. The Skin We’re In (Doubleday Canada, Toronto, 2020), 31-32.